CPython Internals: Garbage Collection Basics

CPython manages the memory by using a garbage collector, where the garbage collector relies on the reference counting with a cycle detection algorithm.

All codes in this post are based on CPython v3.10.

Review: Basics of Garbage Collection

Manually managing the dynamic memory area is a risky approach becaus of mistakes that are highly prone to occur. For instance, the program may free the memory that is being used (dangling pointer), or may continue to occupy the unused memory area (memory leak). To prevent these errors as possible, modern programming languages have a memory management system that automatically frees the memory blocks.

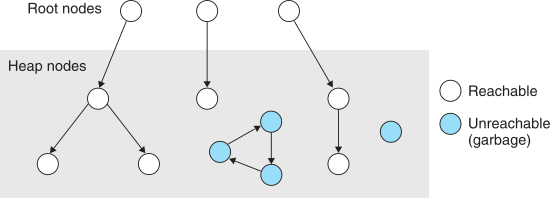

A garbage collector (GC) is a system that periodically frees the unreachable memory. Since the unreachable memories can never be used anymore, it's safe to free the garbage at any point in time. To effectively free the unreachable memories, GC internally maintains the auxiliary status of memory reachability.

Reference Counting

Most basic method is reference counting. All CPython objects PyObject have a field ob_refcnt that stores the number of references that point to themselves.

typedef struct _object {

Py_ssize_t ob_refcnt; // reference count

PyTypeObject *ob_type; // pointer to concrete type

} PyObject;

typedef struct _typeobject {

PyObject *tp_alloc(PyTypeObject *, Py_ssize_t);

int tp_is_gc(PyObject *);

int tp_clear(PyObject *);

void tp_dealloc(PyObject *)

void tp_finalized(PyObject *)

void tp_free(void *); // low-level free-memory routine

// call visitproc for all referencing objects

int tp_traverse(PyObject *, visitproc, void *);

/* ... */

} PyTypeObject;

typedef int (*visitproc)(PyObject *, void *);

When the ob_refcnt becomes 0, it implies that the object is unreachable and thus CPython immediately deallocates the occupied memory area. It seems nice, but the problem is that it cannot handle reference cycles:

>>> container = []

>>> container.append(container)

>>> sys.getrefcount(container)

3

>>> del container # never falls to 0 due to its own internal reference

One could think that cycles are uncommon, but in reality, there are lots of cycles generated from several causes:

- Data structures like graphs.

- Instances have references to their class. The class references its module and the module contains references to everything that is inside, so this can lead back to the original instance.

- Exceptions. They contain traceback that contain a list of frames that contain the exception itself.

- Module-level functions. To resolve global variables, they reference the module which contains references to module-level functions.

Therefore, CPython has gc module for detecting the reference cycle. The main process is defined in Modules/gcmodule.c:L1180-1357.

Extra Memory Layout for Reference Cycle Detection

In order to support the reference cycle detection, the memory layout of objects is altered to accommodate extra information before the normal layout. The additional data store in the head are:

- Pointer for previous and next objects.

- Temporal copy of a reference count.

- Bit masks to denote several statuses.

PREV_MASK_COLLECTING: whether an object has not been visited yet.NEXT_MASK_UNREACHABLEwhether an object is tentatively unreachable._PyGC_PREV_MASK_FINALIZED: whether an object has been already finalized.

typedef struct {

uintptr_t _gc_next;

uintptr_t _gc_prev;

} PyGC_Head; // CPython reuses these fields to hold all necessary info

#define _PyGC_PREV_SHIFT (2)

#define _PyGC_PREV_MASK_FINALIZED (1)

#define PREV_MASK_COLLECTING (2)

#define NEXT_MASK_UNREACHABLE (1)

To employ the extra information, CPython provides two macros (AS_GC and FROM_GC) and wrapper for pymalloc (_PyObject_GC_Alloc).

#define AS_GC(o) ((PyGC_Head *)(o)-1)

#define FROM_GC(g) ((PyObject *)(((PyGC_Head *)g)+1))

static PyObject * _PyObject_GC_Alloc(int use_calloc, size_t basicsize) {

/* ... */

size_t size = sizeof(PyGC_Head) + basicsize;

PyGC_Head *g = (PyGC_Head *)PyObject_Malloc(size);

g->_gc_next = 0;

g->_gc_prev = 0;

/* ... */

PyObject *op = FROM_GC(g);

return op;

}

Identifying Reference Cycles

The code for finding reference cycles is deduce_unreachable at Modules/gcmodule.c:L1069-1146, which requires two disjoint doubly-linked lists as parameters:

base: a list contains objects to be scanned.unreachable: another list contains objects tentatively unreachable.

static inline void deduce_unreachable(PyGC_Head *base,

PyGC_Head *unreachable) {

update_refs(base); // gc_prev is used for gc_refs

subtract_refs(base);

gc_list_init(unreachable);

move_unreachable(base, unreachable); // gc_prev is pointer again

}

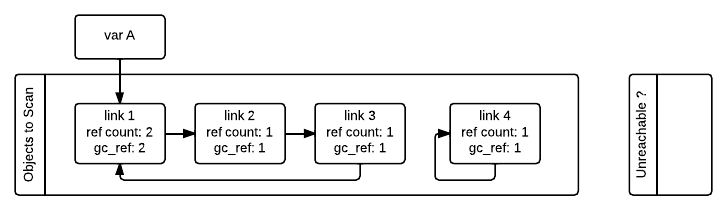

When the GC starts, it scans all the container objects in base and initializes PyGC_Head via gc_reset_refs. The initialization step updates GC's _gc_prev field (gc_ref in the figure) by copying the value of the original reference count ob_refcnt in PyObject (ref count in the figures).

static void update_refs(PyGC_Head *containers) {

PyGC_Head *gc = GC_NEXT(containers);

for (; gc != containers; gc = GC_NEXT(gc))

gc_reset_refs(gc, Py_REFCNT(FROM_GC(gc)));

}

static inline void gc_reset_refs(PyGC_Head *g, Py_ssize_t refs) {

g->_gc_prev = (g->_gc_prev & _PyGC_PREV_MASK_FINALIZED)

| PREV_MASK_COLLECTING // set collecting flag

| ((uintptr_t)(refs) << _PyGC_PREV_SHIFT); // reset refcount

}

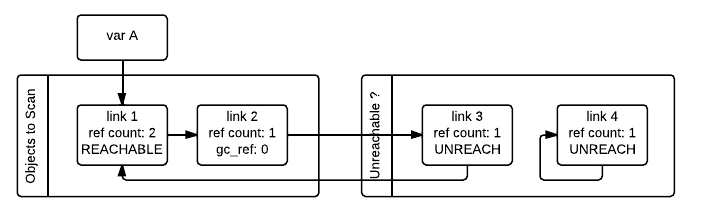

Consider the following memory status as an example.

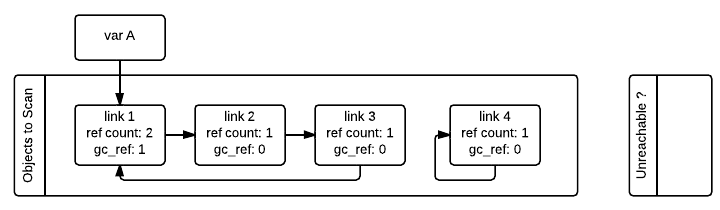

GC then iterates base and decrements the reference count of any other object that the container is directly pointing. After all the objects have been scanned, only the objects that have references from outside will have gc_refs > 0.

static void subtract_refs(PyGC_Head *containers) {

PyGC_Head *gc = GC_NEXT(containers);

for (; gc != containers; gc = GC_NEXT(gc)) {

PyObject *op = FROM_GC(gc);

(Py_TYPE(op)->tp_traverse)(

FROM_GC(gc),

(visitproc)visit_decref,

op);

}

}

static int visit_decref(PyObject *op, void *parent) {

PyGC_Head *gc = AS_GC(op);

if (gc_is_collecting(gc)) gc_decref(gc);

return 0;

}

After applying subtract_refs, the memory is in a state as shown in the following figure. Note that, as you can see below, gc_refs == 0 does not imply that the object is unreachable.

Finally, GC finds all unreachable objects by calling move_unreachable. move_unreachable re-scans all objects in base and does the following:

- When encounters an object with

gc_refs > 0, first it marks the object as reachable. Then, it traverses all objects that are directly reachable from the object and does the following:- Increases

gc_refsifgc_refs == 0, so the objects can be marked as reachable later. - If some objects are in

unreachable, move tobase.

- Increases

- When encounters an object with

gc_refs == 0, it moves the object frombasetounreachableand mark as unreachable.

Once all the objects are scanned, the GC knows that all container objects in unreachable are actually unreachable and can thus be collected.

// some variable names differ from original codes, to enhance human readability

static void move_unreachable(PyGC_Head *base, PyGC_Head *unreachable) {

PyGC_Head *prev = base; PyGC_Head *curr = GC_NEXT(base);

while (curr != base) {

if (gc_get_refs(curr)) { // gc_ref > 0

PyObject *op = FROM_GC(curr);

(Py_TYPE(op)->tp_traverse)(

FROM_GC(curr),

visit_reachable,

(void *)base);

_PyGCHead_SET_PREV(curr, prev); // relink gc_prev to prev element.

gc_clear_collecting(curr); // mark as visited

prev = curr;

} else { // gc_ref == 0

prev->_gc_next = curr->_gc_next;

// no need to curr->next->prev = prev because it is single linked

// moves curr from base to unreachable & mark as unreachable.

PyGC_Head *last = GC_PREV(unreachable);

last->_gc_next = (NEXT_MASK_UNREACHABLE | (uintptr_t)curr);

_PyGCHead_SET_PREV(curr, last);

curr->_gc_next = (NEXT_MASK_UNREACHABLE | (uintptr_t)unreachable);

unreachable->_gc_prev = (uintptr_t)curr;

}

curr = (PyGC_Head*)prev->_gc_next;

}

base->_gc_prev = (uintptr_t)prev;

// don't let the pollution of the list head's next pointer leak

unreachable->_gc_next &= ~NEXT_MASK_UNREACHABLE;

}

static int visit_reachable(PyObject *op, PyGC_Head *reachable) {

PyGC_Head *gc = AS_GC(op); const Py_ssize_t gc_refs = gc_get_refs(gc);

if (! gc_is_collecting(gc)) return 0; // ignore visited objects

if (gc->_gc_next & NEXT_MASK_UNREACHABLE) { // object in unreachable

/* remove current object from unreachable */

PyGC_Head *prev = GC_PREV(gc);

PyGC_Head *next = (PyGC_Head*)(gc->_gc_next & ~NEXT_MASK_UNREACHABLE);

prev->_gc_next = gc->_gc_next;

_PyGCHead_SET_PREV(next, prev);

/* ... and append to base */

gc_list_append(gc, reachable);

gc_set_refs(gc, 1);

} else if (gc_refs == 0) { // object in base and gc_ref == 0

gc_set_refs(gc, 1);

}

return 0;

}

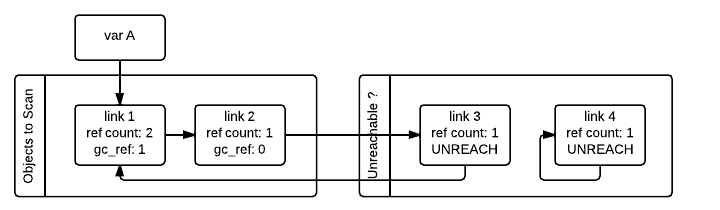

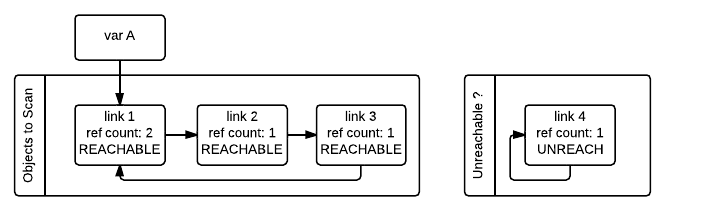

Following image depicts the state of the lists in a moment when the GC processed the link_3 and link_4 but has not processed link_1 and link_2 yet.

Then GC scans link_1 and marks as reachable.

After that, GC scans link_2 and this moves link_3 from unreachable to base. GC finally scans link_3 and mark it as reachable and the process is finished.

Note that no recursion is required by any of this process, and neither does it in any other way require additional memory, except for \(O(1)\) storage for internal C needs.

References

- Randal E. Bryant and David R. O'Hallaron, Computer Systems: A Programmer's Perspective (3/E).

- Pablo Galindo Salgado, Design of CPython's Garbage Collector